0000-0002-0692-3485

0000-0002-0692-3485  glendayamilethtrejo@gmail.com

glendayamilethtrejo@gmail.com

Mendive. Journal on Education, July-September 2025; 23(3), e4067

Translated from the original in Spanish

Original article

Research skills in elementary school children in a public school in El Salvador

Competencias investigativas en niños y niñas de educación básica en una escuela pública de El Salvador

Competências investigativas em crianças do ensino básico numa escola pública de El Salvador

Glenda Yamileth Trejo Magaña1  0000-0002-0692-3485

0000-0002-0692-3485  glendayamilethtrejo@gmail.com

glendayamilethtrejo@gmail.com

1 University of Sonsonate. El Salvador.

Received: 19/12/2024

Accepted: 3/07/2025

ABSTRACT

This study analyzed the research competencies of fifth-grade students at a public school in El Salvador, where structural, methodological, and material limitations persist that restrict the development of scientific thinking. The objective was to diagnose strengths and weaknesses in the cognitive, procedural, and communicative dimensions of these competencies. A mixed-method approach was applied with 27 students and two teachers, using diagnostic tests, focus groups, and interviews. Quantitative data were analyzed with JASP software (t test), and qualitative data were triangulated to validate findings. A favorable attitude toward research was identified (56% associated it with "asking questions"), although with difficulties in formulating hypotheses and analyzing results. There were no significant differences by gender (t = -0.003; p = 0.998). Teachers' voices revealed decontextualized curricula, lack of resources, and limited family involvement. It is concluded that fostering research competencies requires transforming the pedagogical approach from a critical perspective, overcoming reproductive practices and promoting meaningful school experiences. The observed gender equity presents opportunities to design inclusive interventions that strengthen not only scientific skills but also the development of reflective citizenship from childhood.

Keywords: scientific literacy; basic education; research skills; scientific method; critical thinking; educational resources.

RESUMEN

El estudio analizó las competencias investigativas en estudiantes de quinto grado de una escuela pública en El Salvador, donde persisten limitaciones estructurales, metodológicas y materiales que restringen el desarrollo del pensamiento científico. El objetivo fue diagnosticar fortalezas y debilidades en las dimensiones cognitivas, procedimentales y comunicativas de dichas competencias. Se aplicó un enfoque mixto con 27 estudiantes y dos docentes, utilizando pruebas diagnósticas, grupos focales y entrevistas. Los datos cuantitativos se analizaron utilizando el software JASP (prueba t), y los cualitativos se triangularon para validar hallazgos. Se identificó una actitud favorable hacia la investigación (56 % la asoció con "hacer preguntas"), aunque con dificultades en la formulación de hipótesis y en el análisis de resultados. No hubo diferencias significativas por género (t = -0.003; p = 0.998). Las voces docentes evidenciaron currículos descontextualizados, falta de recursos y escasa participación familiar. Se concluye que fomentar competencias investigativas requiere transformar el enfoque pedagógico desde una perspectiva crítica, superando prácticas reproductivas y promoviendo experiencias escolares con sentido. La equidad de género observada plantea oportunidades para diseñar intervenciones inclusivas que fortalezcan no solo habilidades científicas, sino también la formación de ciudadanía reflexiva desde la infancia.

Palabras clave: alfabetización científica; educación básica; habilidades investigativas; método científico; pensamiento crítico; recursos educativos.

RESUMO

O estudo analisou as competências de investigação em alunos do quinto ano de uma escola pública em El Salvador, onde persistem limitações estruturais, metodológicas e materiais que restringem o desenvolvimento do pensamento científico. O objetivo foi diagnosticar pontos fortes e fracos nas dimensões cognitivas, procedimentais e comunicativas dessas competências. Foi aplicada uma abordagem mista com 27 alunos e dois professores, utilizando testes diagnósticos, grupos focais e entrevistas. Os dados quantitativos foram analisados utilizando o software JASP (teste t), e os qualitativos foram triangulados para validar os resultados. Foi identificada uma atitude favorável à investigação (56% associou-a a "fazer perguntas"), embora com dificuldades na formulação de hipóteses e na análise dos resultados. Não houve diferenças significativas por gênero (t = -0,003; p = 0,998). As vozes dos professores evidenciaram currículos descontextualizados, falta de recursos e pouca participação familiar. Conclui-se que fomentar competências investigativas requer transformar a abordagem pedagógica a partir de uma perspectiva crítica, superando práticas reprodutivas e promovendo experiências escolares com sentido. A equidade de gênero observada apresenta oportunidades para projetar intervenções inclusivas que fortaleçam não apenas as habilidades científicas, mas também a formação de cidadãos reflexivos desde a infância.

Palavras-chave: alfabetização científica; educação básica; habilidades de investigação; método científico; pensamento crítico; recursos educacionais.

"A scientist is a child who never grew up"

Neil DeGrasse Tyson

INTRODUCTION

The Salvadoran education system faces structural challenges that compromise educational quality and the development of essential skills in students. Research skills in particular -fundamental for cultivating critical thinking, problem-solving, and scientific literacy from childhood- are affected by multiple systemic limitations. These restrictions create significant gaps in learning processes, especially among children.

The national educational situation shows worrying indicators: with an average schooling of just seven grades, limited and discontinuous access to the education system is evident. This situation is exacerbated in rural contexts, where historical inequalities persist associated with factors such as poverty, school dropout rates, and insufficient investment in teacher training and pedagogical infrastructure (Sosa, 2022). These structural conditions directly impact educational quality, hindering the development of key skills such as hypothesis formulation, data analysis, and scientific inquiry.

Recent research (Ballesteros & Gallego, 2022; Sánchez-Castaño et al., 2015) confirms that the predominance of traditional methodologies, focused on the one-way transmission of content, hinders the acquisition of basic scientific skills. This pedagogical approach limits students' ability to understand complex phenomena and apply the scientific method, thus perpetuating deficiencies in their research training.

These barriers are composed by contextual factors such as limited family involvement and unequal access to technological resources, which, according to Paolini et al. (2017), reduce opportunities to develop critical thinking and independent inquiry skills. This combination of factors widens educational gaps and limits learning potential.

Given this situation, this study seeks to diagnose the development of research skills in fifth-grade students at a Salvadoran public school. The objective is to identify both existing capacities and pending challenges, considering the various factors that influence this process. The findings aim to inform innovative pedagogical proposals that foster scientific thinking from basic education, contributing to more equitable education in line with current demands.

Research competencies and investigative skills

In the context of basic education, research competencies constitute an integrated set of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values that enable individuals to conduct research effectively in different contexts. These competencies transcend the mastery of practical skills by incorporating theoretical knowledge, ethical principles, and the ability to apply knowledge in diverse situations. Their development involves not only specific actions, such as the design of experiments or the formulation of hypotheses, but also the mobilization of internal resources -such as prior knowledge and attitudes- along with external resources, such as information networks and pedagogical support (Briceño, 2009).

These elements are deeply linked to advanced cognitive processes, such as critical analysis and rigorous evaluation of evidence, which, according to Ballesteros and Gallego (2022), are essential for scientific literacy and the development of critical citizens in contexts where structural gaps in access to quality education persist. This perspective takes on particular relevance in El Salvador, where the educational system faces serious difficulties in fostering complex thinking skills from the earliest stages of schooling. Accordingly, Bunge (2001) affirms that science demands rational, systematic, and evidence-based thinking, capacities that can only be fostered if the educational environment offers favorable conditions for experimentation, critical reflection, and access to relevant resources. The absence of these elements in many public schools in the country reinforces the urgent need to rethink the curriculum and the pedagogical strategies that guide teaching.

Within this framework, research skills are an essential component of the aforementioned competencies and encompass processes such as inference, systematic observation, data analysis, interpretation of results, and hypothesis formulation. These skills can be developed through consistent practice and appropriate teacher support. Moreno (2005) groups them into perceptual, instrumental, and cognitive skills, which enable students to interpret statistical graphs, use data collection techniques, and communicate findings in a structured and relevant manner.

In order to illustrate the relationship between competencies and research skills, a comparative framework was designed (see Table 1), which allows us to delimit their scope and levels of complexity. While skills focus on specific technical tasks, competencies integrate this practical knowledge into a broader framework that includes attitudinal, ethical, and contextual elements. Thus, a student could learn to write a hypothesis as a specific skill, but only through the acquisition of competencies will they be able to design a complete research project with logical meaning, a defined purpose, and an appropriate methodological approach.

This integrative nature of competencies is especially relevant in basic education, where strengthening scientific thinking becomes urgent given the low results on national assessments. As evidenced by the PAES and AVANZO tests, less than 10% of students achieve superior performance levels in areas requiring critical thinking and problem-solving. These deficiencies reflect an alarming gap in the development of advanced cognitive skills, which in turn underscores the need to transform pedagogical approaches and teaching strategies from the earliest stages of formal education.

Thus, training in scientific thinking should not be understood as an accumulation of data, but as a process that involves systematic observation, causal reasoning, the formulation of relevant questions, and the rigorous interpretation of evidence, as proposed by Ballesteros and Gallego (2022). Overcoming current limitations requires pedagogical strategies that link school activities with formal research structures, so that students not only participate in practical experiences, but also understand the theoretical and ethical foundations that support scientific work (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison between investigative competencies and investigative skills

Aspect |

Research skills |

Investigative skills |

Approach |

Holistic: includes knowledge, attitudes and values. |

Technical: focuses on specific tasks of the investigative process. |

Complexity |

It involves integrating skills with other aspects of the process. |

It focuses on specific, more defined skills. |

Temporal scope |

Long-term development in varied contexts. |

Immediate and specific application. |

Relationship with learning |

It requires comprehensive learning (cognitive, procedural, attitudinal). |

More dependent on practice and technical training. |

Practical example |

Design a complete research project. |

Write a hypothesis or tabulate survey data. |

Research skills constitute a fundamental element within research competencies, but the latter encompass a broader and more comprehensive view. While skills focus on specific tasks in the research process, competencies are incorporated within an ethical and contextual framework that allows for addressing diverse and complex situations. In basic education, strengthening research competencies and scientific thinking is essential to addressing current challenges. However, the results of the PAES and AVANZO tests reveal significant limitations in their development, as less than 10% of the students assessed reached higher levels of performance. This reflects a worrying gap in the development of advanced cognitive skills, underscoring the need to improve pedagogical approaches and teaching strategies to foster critical thinking and scientific inquiry from an early age.

According to Ballesteros and Gallego (2022), scientific thinking goes beyond the simple accumulation of information, as it involves essential processes such as systematic observation, causal reasoning, and the formulation of meaningful questions. However, these capacities face serious limitations in the Salvadoran context. This situation is reflected in the results of the AVANZO test, where the majority of students had difficulty applying their knowledge to solve complex problems.

In basic education, these competencies and skills are essential for fostering critical thinking and scientific literacy. However, studies underscore the need for pedagogical strategies that link classroom activities with structured inquiry processes, ensuring that students not only engage in practical activities but also understand the theoretical and ethical principles that underpin them.

The boy and the girl as scientists

The constructivist perspective recognizes that scientific thinking manifests itself from the earliest stages of child development, when children demonstrate a natural inclination toward exploration, asking questions, and seeking explanations about their environment. This innate curiosity constitutes a fundamental basis for the development of investigative skills, provided the educational context offers structured opportunities for its reinforcement. Authors such as Briceño (2009) maintain that children's scientific thinking, although incipient, encompasses complex cognitive processes that include the formulation of basic hypotheses, the design of systematic observations, and the revision of ideas based on evidence. These capacities not only promote logical reasoning but also lay the foundation for a critical attitude toward knowledge.

Empirical research has shown that, even before formal schooling, children possess cognitive skills that allow them to establish causal relationships and make basic inferences. Gopnik and Meltzoff (1998) demonstrated that children develop intuitive theories about their environment, which they progressively modify through observation and experimentation. These findings suggest that metacognitive processes can be cultivated from an early age when provided with appropriate stimuli. Along these same lines, Puche Navarro (2000) introduced the concept of "enhancing rationality," which describes how children adjust their explanations of the world as they broaden their experiences, thus becoming active agents of their own learning.

However, the full development of these potentialities requires intentional pedagogical intervention. The traditional curriculum, focused on the mechanical repetition of content, often underutilizes children's natural investigative capacity. In contrast, an approach based on scientific inquiry promotes guided exploration, reflective questioning, and collaborative knowledge construction. The teacher's role is fundamental in this process, as they must design learning experiences that transform spontaneous curiosity into structured investigative skills. This entails creating environments where students can observe phenomena, ask questions, contrast ideas, and communicate their findings, always supported by teaching strategies appropriate to their developmental level.

In contexts like El Salvador, where structural limitations persist in the education system, implementing methodologies that foster scientific thinking from the earliest years is a priority. Evidence shows that, even in conditions of limited resources, children can develop basic research skills when provided with opportunities to experiment, debate, and reflect. Achieving this requires not only teachers trained in active approaches, but also educational policies that prioritize early scientific literacy as a tool to reduce learning gaps. Investment in teacher training, adapted materials, and safe spaces for exploration is key to transforming classrooms into environments where children can now exercise their capacity to think and act as scientists.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The research was conducted using a mixed-method approach, combining quantitative and qualitative methods to gain a comprehensive understanding of the research competencies of fifth-grade children in a public school in El Salvador. This approach is based on pragmatic philosophy and seeks to delve deeper into the analysis of complex educational phenomena. The research is framed within the participatory action research (PAR) paradigm, which encourages the active participation of stakeholders to generate transformative knowledge.

Research design

The design combined qualitative and quantitative elements to triangulate data and validate findings, following a triangulation model in mixed methods studies.

Participants

The population consisted of 27 fifth-grade students and two teachers from the selected school.

Data collection techniques and instruments

Statistical analysis

The quantitative data obtained from the diagnostic test were processed using JASP software, which allowed for descriptive analyses. Frequencies, percentages, and correct answer rates were calculated, identifying differences in investigative skills disaggregated by gender. This analysis provided a clear view of the disparities and performance patterns between boys and girls, enriching the interpretation of the findings.

Procedures

The activities were conducted under strict ethical standards, including informed consent from participants and their legal guardians. The strategies employed ensured an environment of trust and respect, maximizing the active participation of students and teachers.

The combination of methods and the integration of multiple perspectives not only allowed us to diagnose the current state of research competencies, but also generated a reflective process to propose strategies aimed at strengthening these skills in the educational context.

RESULTS

This section presents the most relevant findings of the study, aimed at analyzing research competencies in elementary school children in a Salvadoran public context. The results were organized around four key dimensions: cognitive, procedural, and communicative skills, and research motivation. This approach provided a comprehensive view of students' abilities and perceptions, as well as the structural constraints that influenced their development.

The integration of quantitative and qualitative methods in the analysis strengthened the understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. On the one hand, success rates on diagnostic tests were statistically evaluated, while on the other, students' perceptions and emotions were analyzed through focus groups. Teachers' perspectives were also incorporated through in-depth interviews, which allowed for the identification of barriers and opportunities present in the school context.

The results provided valuable evidence on the current state of investigative competencies and suggested strategic lines for their strengthening (Figure 1).

Cognitive skills in research

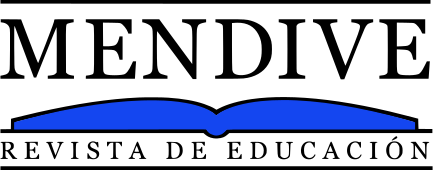

Figure 1. What is research?

The graph illustrates perceptions about the concept of research, highlighting that 56 % of all students identify this process as "asking questions and searching for answers about something unknown." This approach is shared equally by boys (56%) and girls (55%). In other categories, differences are observed: 27% of boys associate research with "looking something up on the Internet," compared to 19% of girls. Similarly, "following a teacher's instructions" was mentioned by 25% of boys and 18% of girls. These data provide a snapshot of the different ways in which students conceive of research, reflecting nuances that may be linked to educational or contextual factors (Figure 2).

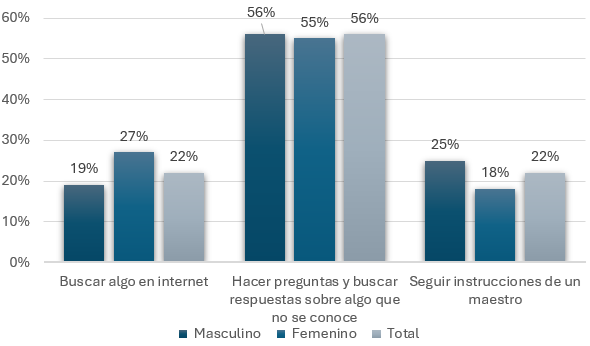

Figure 2. Why is it important to ask questions during an investigation?

The graph shows the reasons students perceive for the importance of asking questions during an investigation, highlighting both general trends and gender differences. An overwhelming majority, 78 % of the total, indicate that asking questions "helps us learn and discover new things," reflecting a widespread appreciation of the cognitive and exploratory value of inquiry. However, significant differences are observed between boys and girls: 82% of girls prioritize this approach compared to 75% of boys, suggesting girls' greater predisposition toward active learning and scientific curiosity.

On the other hand, 19% of the total associate questions with "part of the school rules," which could indicate a more normative or conformist understanding of the research process. This approach is also evenly distributed between genders (19% for boys and 18% for girls). It is interesting to note that only 4% consider asking questions important "because it makes them look good to others," and this perception is exclusively male, although minimal (6%). These differences highlight not only the understanding of research in childhood, but also the possible cultural and educational influences on how questions are valued as a learning tool (Figure 3).

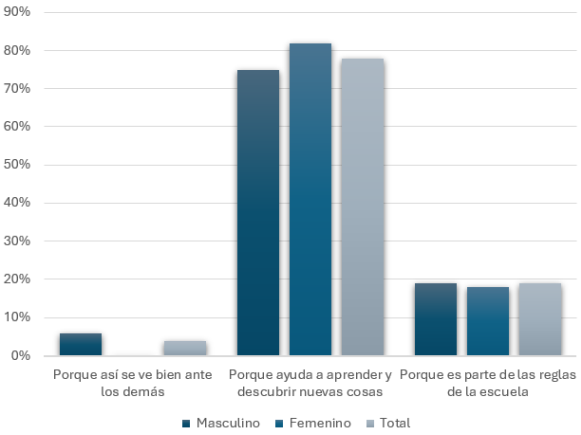

Figure 3. What do you do if the answers you found are different from what you expected?

The graph shows students' responses when faced with unexpected results in their investigations. A majority, 63% of boys, indicate that they try to "understand why they are different," while 36% of girls select this option. On the other hand, 64% of girls prefer to "ask someone else for information," compared to 31% of boys. Only 4% of the total, with no notable gender differences, choose to ignore unexpected answers because they do not consider them relevant. These responses highlight distinct trends in problem-solving approaches among the groups studied (Figure 4).

Procedural skills

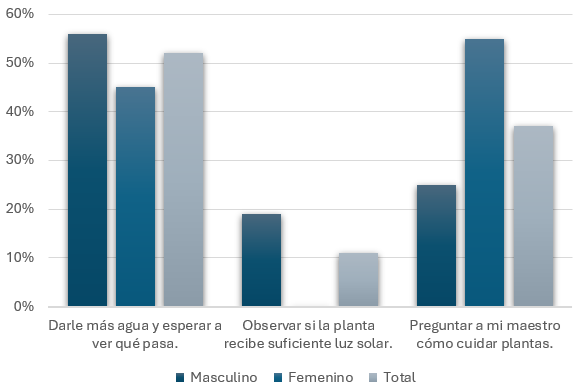

Figure 4. Imagine you want to know why a plant at your school is not growing well.

What would you do first?

The graph shows students' responses when faced with a problem related to plant growth at school. A total of 50% of students indicated they would choose "give it more water and wait and see what happens." When broken down by gender, both boys and girls had similar percentages for this option. In contrast, 30% of boys selected "ask my teacher how to care for plants," while a smaller percentage of girls, 25%, chose this alternative. Finally, the option "observe whether the plant receives enough sunlight" was the least selected, with less than 10% in both groups. These data reflect the students' different initial approaches to addressing practical problems, prioritizing direct action or seeking expert help.

Statistical test

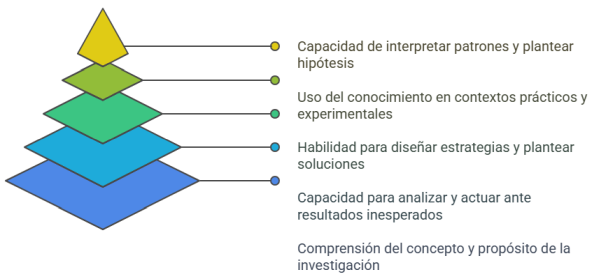

A diagnostic test was developed consisting of 11 items designed to assess the following key areas of research competencies:

Figure 5. Key area in the evaluation of investigative skills

Statistical analysis, performed using an independent samples t-test, revealed no significant differences in the success rate between boys and girls (t = -0.003, p = 0.998). This finding is supported by a 90% confidence interval, whose equivalence limits are between -0.050 and 0.050, indicating that the means of both groups are statistically equivalent. Additionally, the calculated effect size (Cohen's d = -0.003) was practically zero, reinforcing the conclusion that gender is not a relevant factor in the performance of the diagnostic test (Figure 5).

Using a qualitative approach, three focus groups were conducted to explore in-depth the students' experiences, perceptions, and emotions surrounding the research process. These sessions allowed for the identification of common patterns and individual differences that enrich the understanding of research learning through the voices of the participants themselves.

Previous research experiences

When asked if they had conducted research-related activities in school, students offered examples that reflected practical interactions but lacked a formal research structure.

These hands-on activities were valuable in terms of engaging students, but the lack of a pedagogical framework that contextualized the experiences within a formal research framework limited their educational potential.

Limitations in research experiences

Most students agreed that they were rarely assigned research activities. One participant stated, " We've never been allowed to do any research" (Focus Group 1). Instead of fostering structured inquiry skills, homework assignments frequently relied on internet searches, primarily on platforms like Google or YouTube. This reflects a more passive and directed learning approach, which prioritizes obtaining answers over developing critical research skills.

Perceptions on the concept of research

When asked what research means, students offered responses that reflect both curiosity and a limited understanding of the research process:

Although these responses demonstrate an interest in learning, they also reveal a limited understanding of research as a structured process involving problem identification, question formulation, systematic data collection, and critical analysis. This finding reinforces the need to promote a broader and more rigorous understanding of the concept of research in the classroom.

Emotions associated with the research process

The emotions generated around the research ranged from enthusiasm to anxiety, influenced by factors such as previous experiences, the level of available resources, and the guidance received.

Analysis of teacher interviews

Interviews with two elementary school teachers identified critical barriers that limit the development of research skills in elementary school students. The findings, organized into thematic categories, highlight issues that affect both the educational context and the teaching-learning process.

DISCUSSION

The findings reflect both the progress and limitations in the development of research skills in elementary school students, contextualized within El Salvador's public education system. The triangulation of quantitative and qualitative data and the theoretical framework allows for a comprehensive interpretation of these dynamics, considering structural, pedagogical, and contextual factors.

Research competencies, understood as an integrated set of cognitive, procedural, and attitudinal skills (Ballesteros & Gallego, 2022), are in their infancy among the students assessed. Although quantitative results suggest that both boys and girls possess a basic understanding of the concept of research and a favorable disposition toward inquiry, the practical activities carried out lack a solid methodological structure that connects the experiences with formal research processes. For example, while 56 % of students identify research as "asking questions and seeking answers," the activities mentioned, such as building volcanoes or growing beans, are limited to practical experiences disconnected from hypothesis formulation and critical data analysis. This is consistent with the proposals made by González and Fernández (2020), who emphasize the need for pedagogical strategies that link experimental practice with theoretical and ethical principles.

Diagnostic tests revealed that students face significant difficulties in advanced skills, such as problem-solving and interpreting unexpected results. While girls show a greater inclination toward active and collaborative learning, boys tend to adopt more autonomous and exploratory approaches. Although these differences were not statistically significant (t = -0.003, p = 0.998), they reflect cultural and socialization patterns that influence how boys and girls approach research. Furthermore, the scarcity of adequate educational resources, such as laboratories, scientific materials, and assistive technologies, limits the development of procedural skills such as observation, experimentation, and critical analysis. These conditions contribute to perpetuating pedagogical practices focused on rote repetition and memorization, to the detriment of inquiry-based teaching and meaningful learning (Morales et al., 2022).

The family environment emerged as a determining factor in the development of research skills. Low parental involvement, combined with limited educational levels, affects students' preparation for school activities. This aligns with what Paolini et al. (2017) pointed out, who emphasized that collaboration between families and schools is crucial for strengthening cognitive and attitudinal skills from an early age. Furthermore, interviews with teachers revealed a disconnect between educational programs and students' actual abilities.

Teachers expressed that curricular expectations do not fit students' needs, generating frustration among both students and educators. This perception is consistent with Ticas's (2023) analysis, who argues that frequent changes in educational policies limit the implementation of sustainable strategies.

The socioeconomic context and structural deficiencies of the Salvadoran education system represent significant barriers to the development of research skills. The lack of investment in infrastructure, pedagogical resources, and teacher training perpetuates educational and social inequalities (Morales et al., 2022). Furthermore, technological distractions and the lack of regulation regarding the use of devices in the classroom hinder the implementation of effective pedagogical strategies, as Teacher 1 noted in the interviews.

From a theoretical perspective, research competencies require not only practical skills but also an ethical and contextual framework that fosters critical thinking and scientific literacy (Bunge, 2001). However, the results indicate that the Salvadoran educational system lacks the necessary elements to comprehensively promote these competencies. The lack of teacher guidance and a structured pedagogical framework limit students' potential as "little scientists" (Puche Navarro, 2000).

A comprehensive approach is necessary to overcome these barriers. Curricular restructuring is recommended to adapt educational content to students' actual capabilities, accompanied by an investment in educational resources such as scientific materials, laboratories, and accessible educational technologies. Furthermore, teacher training should focus on strengthening research skills and the design of innovative teaching methodologies. It is also essential to promote family involvement through strategies that integrate parents into the educational process and regulate the use of technology to maximize its impact on learning.

The results of this research reflect an educational context marked by structural and pedagogical limitations, but also by significant opportunities to transform teaching and learning in El Salvador. Promoting a comprehensive approach that addresses these barriers from multiple dimensions is essential to ensuring the development of research competencies in elementary school students, thus contributing to strengthening the education system and building a more equitable and critical society.

Based on this analysis, the following actions are proposed to improve the educational context in El Salvador's public schools:

These proposals seek to generate a positive impact on the Salvadoran education system by addressing identified limitations and strengthening students' research capacities through a comprehensive approach. Promoting these strategies contributes not only to children's academic development but also to building a more critical, equitable society prepared for the challenges of the future.

REFERENCES

Ballesteros-Ballesteros, V., & Gallego-Torres, A. P. (2022). De la alfabetización científica a la comprensión pública de la ciencia. Trilogía Ciencia, Tecnología, Sociedad, 14(26), 19-33. https://doi.org/10.22430/21457778.1855

Briceño, T. (2009). El paradigma científico y su fundamento en la obra de Thomas Kuhn. Tiempo y Espacio, 18(58), 15-27. https://ve.scielo.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1315-94962009000200006

Bunge, M. (2001). La ciencia: Su método y su filosofía (Ed. corregida y aumentada, 4.ª ed.). Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana

Gopnik, A., & Meltzoff, A. N. (1998). Words, thoughts, and theories. MIT Press.

Morales, M., Ortiz-Mallegas, S., & López, V. (2022). Violencia escolar, infancia y pobreza: Perspectivas de estudiantes de educación primaria. Pensamiento Educativo. Revista de Investigación Educacional Latinoamericana, 59(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.7764/PEL.59.1.2022.2

Moreno, J. (2005). Habilidades investigativas en la educación superior universitaria de Colombia. Revista de Investigación, 29(58), 101-123. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/8331420.pdf

Paolini, C. I., Oiberman, A., & Mansilla, M. (2017). Desarrollo cognitivo en la primera infancia: Influencia de los factores de riesgo biológicos y ambientales. En Subjetividad y procesos cognitivos (pp. 162-183). Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Puche Navarro, R. (2000). Formación de herramientas científicas en el niño pequeño. Arango Editores.

Sánchez-Castaño, J. A., Castaño-Mejía, O. J., & Tamayo-Alzate, O. E. (2015). La argumentación metacognitiva en el aula de ciencias. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 13(2), 1153-1168.

Sosa, A. (2022). La escuela transformadora que queremos en El Salvador. Ciencia, Cultura y Sociedad, 7(2), 23-39. https://portal.amelica.org/ameli/journal/628/6283432009/6283432009.pdf

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflict of interests.

Authors' contribution

The authors participated in the design and writing of the article, in the search and analysis of the information contained in the consulted bibliography.