Mendive. Journal on Educación, october-december, 2022; 20(4):1219-1236

Translated from the original in Spanish

Original articleMoving towards evaluation as learning

Transitar hacia la evaluación como aprendizaje

Caminhando para a avaliação como aprendizado

Nicole Jara Aguilera1 ![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7639-8041

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7639-8041

Diego Cáceres Cáceres1![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4329-4646

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4329-4646

Valeria León Martínez1 ![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6258-2403

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6258-2403

Carolina Villagra Bravo1 ![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5428-2555

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5428-2555

1 Silva Henriquez Catholic University. Chili.

![]() nicolejaraaguilera@gmail.com; dcaceresc@miucsh.cl; vleonm@miucsh.cl; cvillagrab@ucsh.cl

nicolejaraaguilera@gmail.com; dcaceresc@miucsh.cl; vleonm@miucsh.cl; cvillagrab@ucsh.cl

Received: April 19th, 2022.

Accepted: July 19th, 2022.

ABSTRACT

The present investigation arose from the motivation to generate significant changes in education from the evaluation as learning approach, considering the consequences of traditional practices that have displaced good learning. The objective of this study is to analyze the evaluative practices and forms of teacher leadership in the context of the development of an educational proposal that seeks to transform the pedagogical core to promote deep learning of boys and girls of Basic Education through critical reflection of the own training experiences. Based on a multiple case design and a qualitative perspective, two data collection techniques were used: participant observation and documentary review, and with this framework a content analysis was carried out. The main results show a pedagogical proposal based on the Project-Based Learning methodology, which highlights the importance of feedback during the educational process and learning through a globalizing and contextualized task. One of the most important conclusions is the need to make a profound change in teaching practice, since, in order to transform the pedagogical core from the evaluative approach, the ways of learning and teaching at school must be modified.

Keywords: Self-assessment; self-regulation; evaluation as learning; assessment for learning; teacher leadership; pedagogical core; reflection.

RESUMEN

La presente investigación surgió a partir de la motivación para generar cambios significativos en la educación desde el enfoque de evaluación como aprendizaje considerando las secuelas de las prácticas tradicionales que han desplazado el buen aprendizaje. El objetivo de este estudio es analizar las prácticas evaluativas y las formas de liderazgo docente en el contexto del desarrollo de una propuesta educativa que busca transformar el núcleo pedagógico para propiciar el aprendizaje profundo de niños y niñas de Educación Básica mediante la reflexión crítica de las propias experiencias de formación. A partir de un diseño de casos múltiples y una perspectiva cualitativa se utilizaron dos técnicas de recolección de datos: la observación participante y la revisión documental, y con este marco se realizó un análisis de contenido. Los principales resultados dan cuenta de una propuesta pedagógica que se basa en la metodología de Aprendizaje Basado en Proyectos, donde se destaca la importancia de la retroalimentación durante el proceso educativo y de aprender por medio de una tarea globalizante y contextualizada. Una de las conclusiones más importantes es la necesidad de realizar un cambio profundo de la práctica docente, ya que, para transformar el núcleo pedagógico desde el enfoque evaluativo, se deben modificar las formas de aprender y enseñar en la escuela.

Palabras clave: Autoevaluación; autorregulación; evaluación como aprendizaje; evaluación para el aprendizaje; liderazgo docente; núcleo pedagógico; reflexión.

RESUMO

A presente investigação surgiu da motivação de gerar mudanças significativas na educação a partir da avaliação como abordagem da aprendizagem, considerando as consequências das práticas tradicionais que têm deslocado a boa aprendizagem. O objetivo deste estudo é analisar as práticas avaliativas e as formas de liderança docente no contexto do desenvolvimento de uma proposta educacional que busca transformar o núcleo pedagógico para promover a aprendizagem profunda de meninos e meninas da Educação Básica por meio da reflexão crítica da própria experiências de treinamento. Com base em um desenho de casos múltiplos e uma perspectiva qualitativa, foram utilizadas duas técnicas de coleta de dados: observação participante e revisão documental, e com este referencial foi realizada uma análise de conteúdo. Os principais resultados mostram uma proposta pedagógica baseada na metodologia da Aprendizagem Baseada em Projetos, que destaca a importância do feedback durante o processo educativo e a aprendizagem por meio de uma tarefa globalizante e contextualizada. Uma das conclusões mais importantes é a necessidade de fazer uma mudança profunda na prática docente, pois, para transformar o núcleo pedagógico da abordagem avaliativa, as formas de aprender e ensinar na escola devem ser modificadas.

Palavras-chave: Autoavaliação; auto-regulação; avaliação como aprendizagem; avaliação para aprendizagem; liderança docente; núcleo pedagógico; reflexão.

INTRODUCTION

Idiosyncrasy and meritocracy have affected evaluation, transforming it into a synonym of measurement and/or qualification, which is why it has become a controversial and complex issue for education (Barba-Martín and Hortigüela -Alcalá, 2022; Sanmartí, 2020). Hernández -Nodarse (2017) states that, although in the evaluative field the measurement of conceptual contents has predominated without considering diversity, interests and ways of learning, different types of evaluations determined by certain currents and pedagogical trends have also emerged. In this sense, it is considered necessary to move towards an evaluation approach as learning to achieve, as teachers, promote a powerful learning culture in the school.

The educational transformation to which it aspires seeks to reconfigure the pedagogical nucleus "composed of the teacher and the student in the presence of the contents" (Elmore, 2010, p. 18). In this way, the rigorous examination of what students actually learn can be analyzed from an evaluative perspective, since this practice and its purposes can have contradictory effects on training (Ríos-Muñoz and Herrera-Araya, 2021). Likewise, the usual link between evaluation and application of procedures and instruments leads to a superficial understanding of the formative sense they serve (Muñoz et al., 2016). For this reason, it is considered relevant to analyze evaluation practices and forms of teacher leadership through a process of critical reflection on their own pedagogical experiences.

1. Assessment as learning

Assessment as learning indissociably links assessment and learning processes, and is based on a democratic relationship between the teacher and each student that favors learning to learn (Barba-Martín and Hortigüela -Alcalá, 2022; Cabrera and Soto, 2020; Santos War, 2014). For Sanmartí (2020), evaluation and learning make up a single process, since the evaluation guides the learner and the teacher about the difficulties that arise in the educational process in order to find solutions based on self-assessment for self-regulation. From this evaluative approach, evaluation is one more learning opportunity and, therefore, it is not carried out at specific moments of the educational process, but rather develops naturally when learning.

From a vision of learning as a human practice, Elmore (2019) argues that the future of assessment cannot be separated from the future of learning, and also exposes the challenge of developing assessments that focus on feedback and capacity building. of learner agency over achievement measurement. Along these same lines, Hernández-Nodarse (2017) argues that the formative nature of evaluation has been distorted, since the verification meaning that is given to it tends to judge more than favor learning. For this reason, it seeks to make learning visible in evaluation processes, in order to reflect on the deep meaning, it has in teaching practice.

In accordance with the meaning of evaluation as learning, it has been considered that the proposal of a formative evaluation, described by Sanmartí (2020), is consistent because it emphasizes the logic of the learner, defining it as "that which promotes the student to be who collects the data, analyzes it and makes decisions to overcome obstacles and be able to improve" (p. 36). In this approach, the self-assessment of each student is key as a habitual practice that leads to self-regulation, which is not synonymous with self -assessment.

In a context of formative evaluation in the classroom, the teacher promotes the student to become aware of and control their learning, to this end, guides them to identify and understand the error to learn to learn (Sanmartí, 2020, Santos Guerra, 2021). This feedback process is essential for students to learn to define internal achievement criteria through reflection and dialogue, which fosters the development of a personal sense of what they learn (Lambert, 1995, as cited in Lambert, 2016). In short, this evaluative approach promotes practices that promote democratic learning scenarios where the interaction between student and teacher is based on a horizontal, dialogic and collaborative relationship consistent with the educational purposes that are aspired to (Rincón- Gallardo, 2019).

If what each student actually learns is analyzed, the evaluative dynamic must necessarily be reconsidered, since, if the school does not democratize its practices, the students will not be able to fully develop (Emore, 2010). For this reason, the evaluation that involves the student encourages them to display various types of knowledge, skills and attitudes that help them to function and contribute to life in society.

2. Pedagogy by projects

Schooling has generated certain contradictions because, instead of cultivating the ability and taste for learning, the educational practice of schools has taken pains to train students who are disciplined, obedient and conditioned with respect to what teachers tell them (Rincón- Gallardo, 2019; Ríos-Muñoz and Herrera-Araya, 2021). However, when they are allowed to decide what and how to learn, the ability to think, creativity and motivation are fostered by the satisfaction of learning better (Blanchard and Muzás, 2020; Sanmartí, 2020; Santos Guerra, 2021). From a restricted perspective of pedagogy, focused on the transmission of content to be reproduced in subject evaluations, Rincón (2012), proposes a change in the rigid structure of the traditional educational approach through a more globalized conception of learning that considers the projects as more than a method, with which learning focuses on what is of interest, what makes sense and what is the subject of questions based on situations that occur in the environment and that are related to the curriculum. The learning projects are linked in a coherent way with the formative evaluation approach, creating spaces that promote the autonomy and self-regulation of the student body. Now, to fully advance towards a conception that mobilizes the student to take control of their learning, it is necessary to democratize the evaluation process.

In general, the reading of the curricular guidelines tends to focus on the teaching of basic conceptual and procedural knowledge, limiting the evaluation process, fragmenting knowledge and addressing issues that are far from the interests of students (Rincón, 2012; Ríos-Muñoz and Herrera-Araya, 2021). An innovative proposal is the learning projects that contemplate a more integrated, problematized and contextualized work, in which the participants can tackle a problem in a collaborative way covering different areas of knowledge and experiences (Cyrulies and Shamne, 2021; Blachard and Muzás, 2020). It is relevant to consider that, in a learning project, students have the opportunity to direct their own process in a collaborative setting (Blanchard and Muzás, 2020), in which each teacher assumes a role of teacher and learner (Cabrera and Grove, 2020). In short, collaborative learning deployed in projects fosters the comprehensive education of students for their full development and contribution to society, considering topics of interest that encourage motivation and satisfaction in learning to make decisions autonomously about their educational process.

In a context of collaboration and authentic learning, it is essential to resignify the role of evaluation to promote creative, democratic and co-construction spaces for globalized learning aimed at training critical and self-critical people, who manage to learn to make decisions and promote the development of their emotions, interests and motivations (Blanchard and Muzás, 2020; Ríos-Muñoz and Herrera-Araya, 2021). This vision guides deep learning through practices that mobilize the student as a leader of their learning together with the collaboration of the teacher, who manages to dynamize their role as a co-learner through a dialogical and democratic relationship. Unfortunately for Sanmartí (2020), the evaluation continues to be centered on the teaching staff, since they are the ones who finally make the decisions about what and how to evaluate, for example, they are in charge of creating the evaluation criteria that serve to verify the achievement of the learning objectives. without student collaboration. In consideration of the background and, being in the last stage of initial training as teachers, the research is based on the interest in contributing to the management of significant changes in education. According to the experience sustained as students and as teachers in training, pedagogical situations have been experienced in which the evaluative practice has displaced learning. In this regard, it has been seen how hierarchy fosters competition to the detriment of collaboration, likewise, the punitive sanction for error that silences the learner has been observed and, also, how the qualification is more important than feedback or what is being done. learning. Therefore, to achieve a change in education, it is necessary to become aware of the role as teacher leaders to generate changes that contribute to the transformation of the nucleus from the evaluation approach as learning, that is, the practice of evaluation and learning. as a single and inseparable process. In this way, the interaction between the student, the teacher and the knowledge must be mobilized based on dialogical and horizontal relationships, positioning the learner at the center of the educational process and the teacher as a co-learner.

In view of the above, it is necessary to reflect critically and deeply on pedagogical practices and the ways in which the different agents of the school are linked. Due to the above, this study aims to analyze the evaluative practices and the forms of teacher leadership in the context of the development of an educational proposal that seeks to transform the pedagogical core to promote deep learning of boys and girls of Basic Education through critical reflection. of their own training experiences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Educational research must be an indispensable practice for teachers that encourages them to reflect on current events and needs that arise from the context in which they are inserted, so that it can transform educational practices and encourage students to achieve improvements in their learning. (Bisquera, 2009).

The research with a multiple case study design considers three cases in total, and in each of them there is a teacher in training and their respective educational center of professional practice. Each researcher was in his last semester of initial teacher training to qualify for the title of Professor of Basic Education (Primary) at a private university in the commune of Santiago, capital of Chile. With this design, the pedagogical practices were analyzed with a qualitative methodology (Flick, 2015), through descriptions and holistic reflections with the purpose of understanding the tensions that were generated between the traditional pedagogical actions that are part of the school culture of schools and those practices guided with the approach of evaluation as learning. The data collection was carried out with the following two techniques:

a) Participant observation: The researchers from each context were able to integrate into the educational dynamics of their respective practice centers, observing and participating in the classes. These instances allowed us to focus the observation on the role of the teacher, the role of the student and the types of content that were addressed.

b) Review of documents, records, materials and artifacts: To better understand the environment and the phenomena that occurred in the contexts of practice, the following are used: on the one hand, educational materials, information recorded in the portfolios of each teacher in training professional, visual evidence of the student learning process; and, in parallel, stories or assessments of Basic Education students and teachers in training.

The pedagogical experience itself that sought the development of practices from an evaluation as learning approach was assumed as a starting point. This process was carried out in a framework of intentional and permanent reflection, just as Fullan (2020) states, new behaviors and experiences were thought of for the resignification of beliefs.

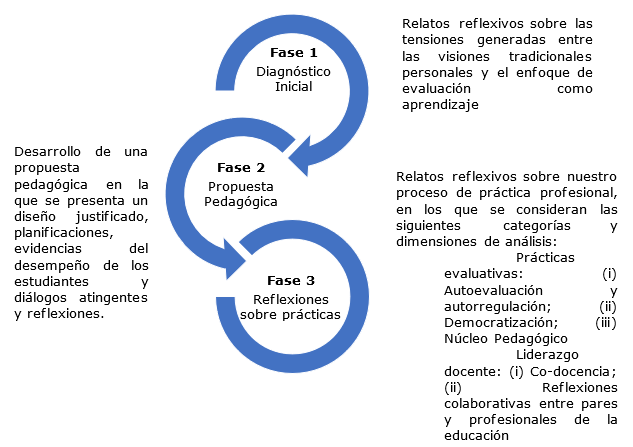

Fig. 1- Phases developed during the research process

The analysis of the information was carried out with the content analysis technique, which consists of a systematic way of interpreting the implicit aspects of the texts under study. This technique is not limited only to interpreting the explicit content of the collected material, but also seeks to delve into the latent and social content of the context.

Table 1- Dimensions of analysis from the assessment as learning approach

Category |

Dimensions reflexive |

Description |

Practices evaluative |

Self -assessment and self- regulation |

Ability to regulate the learning process itself, considering the error as an opportunity, identifying strengths and weaknesses, and developing strategies in order to build a way of learning that can improve over time. |

Democratization |

Generate spaces conducive to learning through dynamic, dialogical and homogeneous relationships between educational actors. |

|

Nucleus pedagogical |

Basic unit of learning that makes up the relationship that develops between the teacher, the student and the content. |

|

Leadership teacher |

Co- teaching |

Instances of collaboration between teachers to build learning designs in order to carry out and evaluate the teaching and learning process. |

Shared reflection with other peers and education professionals |

Intentional and rigorous practice of an individual and/or collective nature that analyzes and evaluates pedagogical visions and actions in order to reconstruct them according to the educational purposes determined by the school community. |

RESULTS

1. Design of the pedagogical proposal according to the evaluation as learning approach

Considering that teaching and learning should not be reduced to the transmission of content and knowledge to be retained, in the pedagogy by projects mentioned by Rincón (2012), a change is proposed for the rigid structure of the educational vision. The author proposes a more globalized conception of learning in which projects are more than a method, since she defines them as a construction of knowledge, experiences and interests of the participants based on the relationships and bonds they form during the process, and not as strict steps.

Project Pedagogy is consistent with the assessment as learning approach, since, according to Blanchard and Muzás (2020), if a challenging task is clearly proposed to students, they will gradually be able to decide the times of individual work, where start, where to go and where to finish. This helps them develop self-regulation and autonomy as they make decisions about their work. In this way, students are the real protagonists and teachers are responsible for mediating the learning situation through effective feedback and teaching resources.

It is important to point out that Pedagogy by projects or Learning Projects (PdA), is often confused with other similar terms, such as Project-Based Learning (PBL). Blanchard and Muzás (2020) explain that a PBL is a strategy that works with problems proposed by the teacher, which may or may not be of interest to the student, and is used at a given time. On the other hand, a Learning Project is a way of teaching and learning with a creative journey led by students, in which they manage to get involved by proposing ideas and making decisions regarding an axis that integrates learning from various areas.

The intention is to continue on the path of Pedagogy by projects, however, if the way of teaching and learning does not change from the root, it will be difficult to change the evaluative approach. Therefore, it was decided to promote the transformation of the pedagogical core with a didactic proposal that was developed from a PBL, which represents an equally challenging and innovative strategy, since this type of methodology had not been participated in or applied. A PBL was applied assuming that, although it is not part of Pedagogy by project, it contributes to understanding the importance of the globalizing task for learning. Part of the transformation requires understanding that addressing content in a fragmented way is not consistent with the training approach, which manages to promote a comprehensive training of students, considering the interest, motivation and usefulness of knowledge for life.

2. Evidence of the implementation of the pedagogical proposal

a) Construction of evaluation criteria in collaboration with students:

To start building the evaluation instrument, students were given the opportunity to choose the evaluation situation, and decided to make an oral presentation. Then, they were told that they would define what a good oral presentation was, and to do so, they were shown a blank table. In this instance, each student mentioned what should be considered for the presentation. It should be noted that they knew what a rubric was, because at school they always socialized them.

All the children participated in the elaboration of the rubric, and each one mentioned different aspect that should be important in it. While this was happening, the teachers focused on guiding this process without intervening, since they were expected to be able to choose what they wanted to learn. During the construction process, the students mentioned that the seasons have "certain colors" due to weather conditions. For example, winter is gray due to clouds and low temperatures, or orange and yellow colors are observed in summer due to high temperatures. Below is the result of the rubric built by the boys and girls based on dialogue and discussion.

Table 2- Analytical evaluation rubric - 2nd Basic Natural Sciences

Criterion |

Accomplished |

moderately Accomplished |

to achieve |

climate characteristics _ |

Explain in detail what the weather is like in each season, mentioning its position on the calendar and whether it is colder or hotter compared to the rest of the year. |

Explain what the weather is like in each season, mentioning its position on the calendar and whether it is colder or hotter compared to the rest of the year. |

Explain with some difficulty what the weather is like in each season, mentioning its position on the calendar and whether it is colder or hotter compared to the rest of the year. |

Significant colors and elements of each season |

Mention the colors that predominate in each season, such as the colors of the plants, the sky, the clothes that people wear, among others, in addition to mentioning some elements that people tend to wear in that season. |

Mention some colors that predominate in each season, such as the colors of plants, the sky, the clothes that people wear, among others, in addition to mentioning some elements that people tend to wear in said season. |

It mentions few of the colors that predominate in each season, such as the colors of plants, the sky, the clothes that people wear, among others, in addition to mentioning few elements that people tend to wear in that season. |

Coherence |

The text presents a logical continuity of events, showing a clear coherence, which facilitates the understanding of the writing. |

The text presents a logical continuity of events, falling into some confusing redactions. |

The text presents ambiguities that hinder the textual progression, showing little coherence, which makes it difficult to understand the writing. |

Cohesion (use of connectors) |

Use the connectors correctly, allowing the text to be very well cohesive. |

Correctly uses the connectors, allowing the text to be moderately well cohesive. |

You repeatedly use some connectors and/or they are used inappropriately. |

Accent, punctual and literal spelling |

Uses spelling correctly, making 1 or 2 errors. |

Uses spelling correctly, making 3 or 4 mistakes. |

Use spelling, making between 5 or 7 errors. |

It is important to expose the error of incorporating qualifying adjectives and quantities to describe and differentiate performance levels, as this does not provide useful information to improve learning orientation. In addition, as Sanmartí (2020) mentions, the primary purpose of said evaluation instrument goes beyond indicating the level of achievement obtained by the student. For example, in the punctual, stress and literal spelling criteria, it can be noted that there is a quantitative differentiation, by explaining that the level of performance is measured with the number of errors and that does not provide the student with a tool that allows him to learn, because it only measures in a punitive way.

b) Socialize a test before the day of the evaluation: According to the school reality of the internship educational center, five semester grades per subject are requested, and this is a reason why we must carry out evaluations with summative intentionality. However, the important thing is that students do not orient their learning to answer a test or obtain a grade, but rather that they understand the meaning of learning for life. After finishing the PBL, it was decided to apply a test on the content addressed in order to show the students' learning from another perspective, taking into consideration that, if they managed to face the challenging context of the PBL, they can apply what they learned in a test.

Sanmartí (2020) points out that knowledge is useless for those who do not know how to apply it, and an evaluation of results should allow corroborating that and not focus on measuring content memorization. For this reason, the test contains questions in which not only the result is evaluated in isolation, but the explanation of the procedures involved is also evaluated. In this way, you can understand the way students understand proportional relationships and their logic to apply them.

In addition, it was decided to incorporate an evaluation criterion with its descriptors in each question to guide the student when answering. Another important decision regarding the evaluation of results was to show, read, comment and resolve doubts about the test together with the students during the class prior to its application in order to make the instrument transparent and avoid that surprise factor that tends to increase nervousness. and student anxiety. The misuse of the concept of evaluation is frequent, and it is associated exclusively with a test or the completion of a process, which generates rejection by students when facing an evaluation situation with summative intentionality. Given this, Santos Guerra (2014) affirms that the evaluation often sows concern among people, whether in the teachers or the students, and he is right in this, since the pressure of a qualification contributes to the negative perception of the evaluation.

Table 3- Analytical rubric extract written test - 7th Basic Mathematics

To answer questions 3.1 and 3.2., be guided by this rubric, where the "Achieved" category shows you how you should answer according to what is expected. |

|||

Indicator |

Accomplished |

moderately accomplished |

missing by achieve |

Recognizes a proportional or non-proportional relationship between ratios based on an everyday situation |

Properly identifies a proportional or non-proportional relationship between ratios, justifying in detail that proportionality is recognized from the constant between the variables or elements that make up the ratios. For example, if the ratio “for every 1 cup of tea there are 2 tablespoons of sugar”, doubles proportionally, it would be: “for every 2 cups of tea there are 4 tablespoons of sugar”. |

It fairly adequately identifies a proportional or non-proportional relationship between ratios, superficially justifying that proportionality is recognized from the constant between the variables or elements that make up the ratios. For example, if the ratio “for every 1 cup there are 2 tablespoons of sugar”, doubles proportionally, it would be: “for every 2 cups of tea there are 4 tablespoons of sugar”. |

Inadequately identifies a proportional or non-proportional relationship between ratios, since the justification lacks recognition of the constant of proportionality between ratios. |

c) The importance of feedback to guide the student: A positive aspect that helps students to guide their understanding is the use of counter-questions to make feedback, trying to constitute a feedforward. Even so, it is necessary to investigate more into the good questions for those students who do respond well and not settle for the approved answer, since the aim is to make a return that arouses their curiosity and encourages learning to learn. At the same time, we must encourage students to ask good questions to co- assess, self-assess, and self-regulate their learning, which gradually decreases dependency on the teacher. Below is an example based on guiding dialogues between students and a teacher:

After reviewing the concept of area of quadrilaterals, some students went to the board and began trying out strategies using the grid to calculate a given area. They realized that counting only the boundary squares matches the perimeter but not the area, so they dropped that option. They then counted the squares on one side and multiplied them by two and, not getting the same given result, they also ruled out that option. Until then, no one had asked the trainee teacher what the answer was and everyone worked autonomously, evaluating their strategies individually or as a group.

Student 2: I know aunt, counting all the pictures.

Teacher-in-training: Come to the board, explain it to us and let's check your strategy.

At that moment, some classmates stood up and went to the blackboard to work with other figures and try the strategies already mentioned.

Teacher in training: So, we have two strategies to calculate the area. The first is multiplying height by width, and the second is counting all the boxes. Let's check if it is so.

A student, who participates for the first time by going to the blackboard says:

Student 2: You can also multiply.

Teacher in training: Multiplying what?

Student 2: (Looks at the three by three grid), three by three; the area is 9.

Teacher in training: Where did you get the 3?

Student 2: If you count that side (point to one of the sides) it's three squares and the other side is also three squares, and 3 times 3 is 9.

Teacher-in-training: Yes, what you just did is fine, and now how can you check it using the grid, using the boxes as you said?

(There was a moment of silence)

Teacher in training: Let's remember what was the definition of area that was discussed in the previous class, what is area?

Student 2: Area is the space used by a figure.

Teacher-in-training: Explain what that means. Think about the area you are going to use in your green space.

Student 3: The area occupied by a figure.

Student 2: Like the floor it occupies.

To get them to really understand that area is the surface of any figure, the teacher intentionally marked the entire surface of one of the figures on the board and repeated the definition: "all this is the area of a figure, it is the space it occupies, as well as the space occupied by the area that they are going to use for their green space".

Teacher-in-training: So how can I calculate the area of these figures using the grid of each of them?

Student 2: Counting each unit, the squares.

Teacher-in-training: Check it out.

Student 2: Auntie, there are 30 frames. That's the area (the grid you used was 6 by 5).

3. Analysis of the evaluative actions and forms of teaching leadership developed during our professional practice

a) Self-assessment and self-regulation: Leaving behind traditional assessment practices in which the teacher is the center has been a great challenge, since in order for the student to develop the ability to learn by themselves, the role of the teacher must become the of a co-apprentice. Although it was not possible to promote self-regulation and self-assessment of the student body fully, it was possible to become aware of its importance. For example, before starting this study, an appropriation of the entire learning process was evident, making many decisions and putting the student off:

Finally, regarding the strategies applied, the activation of prior knowledge is a good strategy to assess students through dialogue and, together with this, it contributes to the monitoring of students in terms of their cognitive processes. However, it is not enough to ask questions or talk with students about a topic or content, it is also necessary for the teacher to observe the process of each student and be aware of it, for example, with a record through a checklist that includes the evaluation criteria that must be achieved in the class or unit. (Professional Practice Portfolio I, Researcher 1)

During the development of the research and the pedagogical proposal, the need to allow students to participate more was understood, so that they could be aware of their learning. In this way, self-assessment and self-regulation were manifested in certain instances where the students were able to recognize their mistakes and collaborate in the learning of their peers, however, most of the time the teachers were the main regulating and guiding agent of the process.

b) Democratization: Considering that students are used to being directed by the teacher because of the conventional school culture, it can be said that we still have to work to achieve spaces that democratize learning. For example, before carrying out this research and delving into the evaluation as learning approach, it was thought that using the list participation system contributed to equity and order within the classroom, as a way of improving learning.

To allow all students to participate, in an orderly and respectful manner, each student is named in order of list, likewise so that this modality is equitable, the list can start ascending, descending or start from the middle. (Professional Practice Portfolio I, Researcher 2)

From the investigation, it was understood that spontaneity and naturalness are part of learning and its democratization. It is highlighted that the dialogical interactions were protagonists during the development of the classes, a situation that encourages the construction of more horizontal relationships between the educational actors based on close links and trust.

c) Pedagogical core: In order to mobilize the pedagogical core, it is necessary to radically change the conceptions about the role of students and teachers and how they jointly approach the contents. Although the roles of the core actors were able to mobilize in certain instances, this was not enough to transform the ways of learning and teaching. The interaction between the teacher and the student needs to be stimulated, giving the latter a space where they can decide on their own learning process. However, there was a significant change in the personal sphere, which was to understand the importance of changing the way of teaching and learning, understanding that learning and evaluation are the same process. Before knowing the formative evaluation approach and the importance of transforming the nucleus, there was a tendency to mechanize the evaluative practice, planning it and limiting it to certain moments of the class, in addition to positioning the teacher as the main evaluating agent of the educational process, for example:

Regarding the evaluation, this is present throughout the class, since the didactic strategies are complemented with the evaluative strategies, allowing the teacher to collect information from the interaction with the students through the activities, mainly using feedback. However, the planning considers two important spaces for formative evaluation during class, a reflective pause after the experiment activity and, finally, metacognition questions and a collaborative summary that considers the main ideas. (Professional Practice Portfolio I, Researcher 1)

d) Co-teaching: The professional practice experience was truly enriching due to the collaborative work carried out between the teachers in training and the head teacher. Reflective sessions were held to develop ideas that pointed towards the evaluation as learning approach. It was possible to plan, build instruments, reflect on personal experiences and resignify professional knowledge based on mutual support. Gradually, the role of apprentice leader was carried out, forming a learning community.

On the other hand, in the practice centers there were few instances where co-teaching could be developed, since more than collaborative work, they assigned tasks such as reviewing papers, tests or carrying out activities. There were no instances where ideas were shared about the approach addressed in this research. When innovative ideas were given, they were questioned, and the justification was that the school reality did not allow it, or else they underestimated the capacity of the students.

Reading the teaching portfolios of professional practices prior to this study shows that collaborative work and co-teaching were absent concepts that were not considered important to improve learning. In this investigative period, the true meaning of forming links between peers to constitute a true learning community was visualized and understood in depth.

e) Reflections shared with other peers and education professionals: The main instances of collective reflection occurred between teachers in training and the head teacher. Reflective sessions were held around pedagogical practices and ways of thinking as a way to help improve pedagogical designs, evaluation instruments and ways of facing school reality. These moments contributed to professional growth. However, the reflective instances with the collaborating teachers and students were scarce. During the last teacher training process, awareness was raised of the importance of collective reflection to improve pedagogical practices, since reflection was previously conceived as a mainly individual process.

4. Final reflections on the pedagogical proposal

This reflection focuses on highlighting ten errors that arose when trying to go from evaluation as verification to evaluation as learning in order to advance and contribute to the transformation of the pedagogical core:

a) The transformation was not achieved. Each of the teachers in training had to transform first in order to change the dynamics of the pedagogical core and, thus, significantly improve learning. Experiencing the evaluation approach as learning is a great challenge that has generated tensions in personal conceptions about the ways of teaching and learning.

b) There is a lack of understanding to differentiate evaluation approaches. Frequently, activities or learning designs were proposed that were apparently consistent with the training approach, however, they still moved between the verification and training approach, since the role of the teacher and not the student continued.

c) Instances of collaboration with the teachers of the educational centers were not generated. On repeated occasions, the weight of the hierarchy was felt for being teachers in practice. This situation silenced the inner voice to share or defend ideas about the personal educational vision. One consequence of this was that, due to the tensions generated between the personal approach and that of the collaborating teacher, the fear of being poorly qualified arose, since innovative ideas are not always well received.

d) Evaluation instruments were built without the collaboration of the students. As teachers with a traditional educational background, it is still difficult to free ourselves from the responsibility of being in control of everything that is done during a class, leaving aside the decisions, emotions, interests and motivations of the students.

e) Evaluation criteria focused mainly on conceptual content were applied. The rubrics carried out focused on evaluating conceptual content and, in this sense, in an evaluation it is important to consider criteria that contribute to the comprehensive training of students, since conceptual, procedural and attitudinal content must be addressed that make sense and serve for life.

f) The rubric did not fulfill the role of guiding student learning. Despite recognizing that evaluation is not an outcome, the mistake was made of not co-constructing the evaluation instrument from the beginning to support and guide the development of PBL. Therefore, the rubric only had the function of corroborating performance.

g) The learning process became mechanized. While trying to understand the formative approach, it was perceived as more difficult than it is. Time was spent searching for teaching strategies and resources, leaving aside the student and moving away from the naturalness so characteristic of the educational process. Instead of liberating learning, it was mechanized trying to control situations that the student should star in and choose.

h) The learning process was fragmented. At first, the pedagogical proposals moved further away from the formative evaluation approach, because an attempt was made to innovate through activities that continued to fragment the learning process. Subsequently, it was understood that the PBL helps to understand the function of a more globalizing task, promoting instances that develop a more comprehensive training of the student and that does not exclusively consider content.

i) The concept of a learning project was confused. It was believed that PBL was a project, but, firstly, it is a methodology that does not have a profound impact on the way of learning and teaching, and, secondly, it does not foster instances of collaboration with students because they were the teachers. who made most of the decisions when designing the PBL without considering their interests and motivations.

j) Self-regulation or self-assessment of the students was not encouraged. It is known that the quality of the feedback to be given to the students is important so that with it they understand what they know and what causes their difficulties. However, adequate mediation was not achieved for them to ask good questions in order to self-evaluate and self-regulate or to co- evaluate and give feedback to each other, which caused them to depend on the teacher's feedback to make decisions.

DISCUSSION

The traditional personal evaluative conceptions were an obstacle to deploy the evaluation approach as learning during the process of professional practice, because as Hernández -Nodarse (2017) states, transforming the evaluative practice is a complex process but possible to develop from the vision of the professional. error as an opportunity to learn, where change means taking the risk of making a mistake and not being content to live in a state of permanent comfort. During the study of the teaching task, personal conceptions about evaluation are questioned, which put in tension the pedagogical approaches that support the practice process. In this sense, as Santos Guerra (2021) states, the tensions that were generated caused critical episodes in which errors were exposed to be analyzed as another opportunity to learn.

If the present investigation is related to the findings of Muñoz et al. (2016), both agree that analyzing their own teaching practices contributes to self- reflection and to moving towards the transformation of entrenched traditional conceptions. In this way, the process of pedagogical reflection is important to generate a change in the way in which the educational process is contemplated, resignifying the learning relationships between the teacher, the student and knowledge. These authors concluded that personal reflection should be considered as a strategy that favors teacher training in the sense that one learns while teaching, evaluating and reflecting.

In coherence with the approach of Elmore (2010), a process of educational improvement was initiated that was fruitful for becoming aware of and controlling professional learning, as well as because a collective learning was chosen beyond the individual, which helped to deepen the reflection and self-assessment of practice. Following this line, the instances of co-design and co-teaching were essential to begin to transform pedagogical practices, in this way, in the daily life of teaching work, it was possible to advance in the resignification of traditional conceptions about teaching, and the learning and evaluation, as Fullan (2020) states "behavior before beliefs" (p. 49). Although it was not possible to move definitively towards the evaluation as learning approach, there were moments in the classes in which the pedagogical nucleus was dynamized, however, these superficial changes were not enough to promote a significant educational transformation.

It is important to highlight that, in the transition towards a conception of evaluation as learning, a PBL pedagogical proposal was designed that allowed, during the implementation process, to account for the permanent role of the teacher, as opposed to the pedagogy by projects proposed by Blanchard and Muzás (2020), since the latter requires a change in the learning culture that could not be fully resignified. In any case, the PBL was a great challenge, by proposing a learning scenario where the resolution of a problem is intended to learn. Now, from this experience, the PBL was proposed from the teacher's point of view, without considering the true interests and motivations of the student body, therefore, the problem posed is not a real challenge that fosters deep student learning.

The study by Hernández- Nodarse (2017) is a benchmark regarding how difficult it is to change rooted educational practices that are part of personal conceptions. The author affirms that there is a disagreement with respect to traditional evaluation practices and a need to position the student at the center of the educational act based on social and educational demands. Complementarily, Muñoz et al. (2016) affirm that the academic vision of evaluation is related to the conception of learning, limiting itself to the reproduction of content and measurement of results. Both studies and this research agree that it is necessary to promote changes in the evaluative vision based on reflective action on practice, democratizing educational spaces where the teacher is a co- learner and a mediator that fosters autonomy, self-regulation and self-assessment. the students, the latter being the true protagonists of the educational process.

Regarding evaluative practices as teachers in training, a greater understanding of the approach of Sanmartí (2020) was needed, who affirms that evaluation and learning are a single process. Unfortunately, authentic learning scenarios were not deployed in the classroom so that the students, together with the teachers, could experience it. As Rincón- Gallardo (2019) exposes, it is complex to completely liberate and transform personal pedagogical practices, due to entrenched conventional visions. Evidence of this was that some assessment instruments were not built collaboratively and were used to check performance instead of guiding and promoting self-regulation and self-assessment by students.

Although mistakes were made, there were still successes that contributed to the transformation of the pedagogical core. One of those transformations already enunciated by Elmore (2010) is the modification of the role assumed by the student to learn. In this framework, one of the teachers in training agreed on the evaluation criteria together with the students to build a rubric to guide learning. This pedagogical decision, shows that it is possible to recognize the student as a true learner, capable of becoming aware of their learning, which professionally challenges to go beyond the joint development of instruments and promote self-regulation of learning throughout the process, as It is proposed by Sanmartí (2020).

Another aspect that should be highlighted were the feedback sessions, which played an important role in pedagogical democratization based on dialogues and discussions between teachers and also in the classroom with students. However, it is important to note that if the teacher is the one who previously validates or approves the decisions that the students want to make, they will not be able to enhance their autonomy.

Finally, it was not possible to develop forms of teacher leadership in schools due to the predominance of vertical relationships between teachers in training and collaborating teachers, given that ideas and opinions were blocked in several instances due to hierarchy and fear. to have a punishment such as a poor evaluation and grade. Clearly, the essence of the stormy academic culture that has not been able to combine with a new learning culture based on dialogue and horizontal professional links emerges. However, there was the opportunity to form a learning community between teachers and their tutor, fostering instances of critical and deep reflection that led to rethinking decisions and convictions. In this way, the main resource for professional learning was the dialogue about personal errors in pedagogical practice.

Finally, it is considered that this research can encourage the development of other studies on the teaching practice itself, as well as serve as an orientation through the results presented as a synthesis of a reflective process that seeks to transform the pedagogical core. In this sense, the approach of errors as learning allows us to guide the path of resignification of the pedagogical beliefs that support the evaluative practice. On the other hand, it highlights the need to move towards a more integrated understanding of assessment and learning as a single process. The foregoing leads to rethinking the way in which evaluation is studied, sometimes disconnected from conceptions, beliefs and educational practice.

Thanks

To the Fondecyt Initiation Project No. 11200738 "Leadership for learning and evaluation practices in Basic Education Schools of La Araucanía", financed by the National Agency for Research and Development of Chile (ANID).

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Barba-Martín. R. y Hotigüela-Alcalá, D. (2022). Si la evaluación es aprendizaje, he de formar parte de la misma. Razones que justifican la implicación del alumnado. Revista Iberoamericana de Evaluación Educativa, 15(1), 9-22. https://doi.org/10.15366/riee2022.15.1.001

Bisquerra, R. (2009). Metodología de la investigación educativa. Madrid: La Muralla.

Blanchard, M. y Muzás, M. (2020). Cómo trabajar con proyectos de aprendizaje en educación infantil. Madrid: Narcea.

Cabrera, V. y Soto, C. (2020). ¿Cómo aprendemos? El docente enseñante y aprendiz que acompaña a los estudiantes en su exploración hacia el (auto)aprendizaje. Profesorado, 24(3), 269-290. https://doi.org/10.30827/profesorado.v24i3.8155

Cyrulies, E. y Schamne, M. (2021). El aprendizaje basado en proyectos: una capacitación docente vinculante. Páginas De Educación, 14(1), 01-25. https://doi.org/10.22235/pe.v14i1.2293

Elmore, R. (2010). Mejorando la escuela desde la sala de clases. Santiago: Fundación Chile.

Elmore, R. (2019). The Future of Learning and the Future of Assessment. ECNU Review of Education, 2(3), 328-341. https://doi.org/10.1177/2096531119878962

Flick, U. (2015). El diseño de la investigación cualitativa. Madrid: Morata.

Fullan, M. (2020). Liderar en una cultura de cambio. Madrid: Morata.

Hernández-Nodarse, M. (2017). ¿Por qué ha costado tanto transformar las prácticas de evaluación del aprendizaje en el contexto educativo? Ensayo crítico sobre una patología pedagógica pendiente de tratamiento. Revista Electrónica Educare, 21(1), 1-27. https://doi.org/10.15359/ree.21-1.21

Lambert, L. (2016). El liderazgo constructivista: forjar un camino propio en pos de la reforma escolar. En C. Díaz (Ed.), Liderazgo educativo en la escuela. Nueve miradas (pp. 227-252). Ediciones Universidad Diego Portales. https://liderazgoeducativo.udp.cl/cms/wpcontent/uploads/2020/04/Liderazgo-Educativo-en-la-Escuela-Nueve-miradas.pdf

Muñoz, J., Villagra, C. y Sepúlveda, S. (2016). Proceso de reflexión docente para mejorar prácticas de evaluación del aprendizaje en el contexto de la educación para jóvenes y adultos (EPJA). FOLIOS, (44). 77-91. Recuperad de: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?pid=S0123-48702016000200005&script=sci_abstract&tlng=es

Rincón, G. (2012). Los proyectos de aula y la enseñanza y el aprendizaje del lenguaje escrito. Red Colombiana para la Transformación de la Formación Docente en Lenguaje. Disponible en: http://www.lenguaje.red/docs/2020/Los_proyectos_de_aula_y_ensenanza.pdf

Rincón-Gallardo, S. (2019). Liberar el aprendizaje. El cambio educativo como movimiento social. México: Grano de sal.

Ríos-Muñoz, D. y Herrera-Araya, D. (2021). Contribución de la evaluación educativa para la formación democrática y transformadora de estudiantes. Revista Electrónica Educare, 25(3), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.15359/ree.25-3.40

Sanmartí, N. (2020). Evaluar y aprender: Un único proceso. Barcelona: Octaedro.

Santos Guerra, M. (2014). La evaluación como aprendizaje. Cuando la flecha impacta la diana. Madrid: Narcea.

Santos Guerra, M. (2021). La evaluación como aprendizaje: la fertilidad del error. En R. Malagón (Ed.), Evaluación y aprendizaje en contextos lasallistas. Experiencias docentes (pp. 43-76). Unisalle. https://ciencia.lasalle.edu.co/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1087&context=libros

Conflict of interests:

The authors declare not to have any interest conflicts.

Authors contribution:

The authors have participated in the design and writing of the work, and analysis of the documents.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

Copyright (c) Nicole Jara Aguilera, Diego Cáceres Cáceres, Valeria León

Martínez, Carolina Villagra Bravo